Ōtata Island

The largest of the island group, Ōtata rises to 67 m above sea level and comprises 35 acres. It’s evident that in the past iwi used the island extensively for the harvesting of birds, fish, and shellfish as there’s a large midden on the flat area above the main beach.

Along with Motuhoropapa, Ōtata appears to have always had a form of forest cover. The forest on Ōtata is dominated by pohutukawa, houpara and emerging kohekohe.

Much of the vegetation on Ōtata was destroyed by an accidental fire in the late 1920s, but it has had over 80 years to recover. Considerable time has been spent weeding over many years by the Neureuter family and many others to ensure indigenous vegetation cover on Ōtata can thrive. Regular weeding efforts ensure species like rhamnus, moth plant, phoenix palm and other weeds have been maintained to low levels. This work will continue to be ongoing while there is a high presence of these weed species on neighbouring islands. As with Motuhoropapa, Ōtata has been rodent free since 2002.

Maintaining the pest free status of The Noises is essential given that many of the resident native species are ground dwelling and ground nesting. This includes burrowing seabirds such as the oi/grey-faced petrel, takahikare/white-faced storm petrels and korora/little blue penguin, and terrestrial species such as the common gecko, flax snail and wētāpunga.

New Zealand native land bird species on Ōtata in approximate order of threat category include kakariki, kaka, bellbird, variable oystercatcher, shining cuckoo, tui, morepork, fantail, grey-warbler, and silvereye. Non-natives include blackbird, thrush, starling, sparrow, chaffinch, greenfinch, goldfinch, and brown quail.

Ōtata Island. Photo: Jason Hosking.

Motuhoropapa Island

Motuhoropapa is one of the few islands in the inner Hauraki Gulf which is still completely covered by indigenous forest and scrub, with most of the slopes and cliffs being occupied by pohutukawa, kohe kohe and karo.

The vegetation contrasts substantially with that of neighbouring Ōtata Island, possibly due to there being no significant known fires on the Island.

In the 1970s the New Zealand Wildlife Service approached the Neureuter family for permission to build a basic hut on the island which was used for research by Dr Phil Moors and others. Their studies (from 1977-1983) considered the biology and effects of the Norwegian Rat on native flora and fauna on offshore islands, and pioneered rat eradication knowledge that is still used today. Further studies were undertaken by Dr James Russell (University of Auckland) on the invasion ecology and genetics of Norwegian Rats (2007) and, then joined by the Department of Conservation, analysis on how invasive rats disperse to and invade offshore islands, as well as examining methods to detect and prevent the arrival of rats on islands (2008).

In 2014, Don McFarlane and Ben Goodwin from the Auckland Zoo surveyed Motuhoropapa and Ōtata to determine whether the habitat was suitable for wētāpunga. In 2015, the first release of approximately 1,000 wētāpunga was carried out on Motuhoropapa Island, and with subsequent releases, the wētāpunga population on the island is considered thriving.

Native flax snails/pūpūharakeke also live on Motuhoropapa.

Motuhoropapa Island. Photo: Joseph Neureuter.

Ruapuke/Maria Island

This is where the dream of predator-free New Zealand began.

In 1960, Ruapuke/Maria Island was successfully cleared of rats that had been decimating the population of takahikare/white-faced storm petrels. In 1964, the island and the nearby David Rocks were declared the first islands in the world to have rodents permanently eradicated from them, a new idea for conservation science.

The approach to rat eradication became a model for other rat and predator eradication programmes globally.

The island is honeycombed with burrows of five seabird species including the oi/grey-faced petrel, kuaka/northern diving petrel, pakaha/fluttering shearwater, korora/little blue penguin, and takahikare/white-faced storm petrels.

In the case of the takahikare, Ruapuke/Maria Island is one of only six confirmed breeding sites of the species within the greater Hauraki Gulf region.

The island was used for bombing practice during the Second World War. Its crest was cleared for the installation of a navigation light in the 1950s. This may have led to introduced weed species which are still to this day very hard to control. Regular weed eradication occurs on the island, which is just over three acres in size.

Ruapuke/Maria Island. Photo: Ethan Kearnes.

Marine environment

The marine environment surrounding The Noises has high biological diversity occurring over a small geographical area, making this area quite precious in the context of the wider Hauraki Gulf. The Noises contain a mix of the clear outer Hauraki Gulf waters and more turbid inner Gulf waters. This creates an unusual mix of ecosystems meaning in effect The Noises are like the outer islands but located within the inner Hauraki Gulf.

High tidal currents that encompass and influence the Islands correlates with the area being popular for fishing (customary, recreational and commercial). The Islands also currently support a range of marine species (particularly bivalves) many of which are in serious decline across the wider Hauraki Gulf.

In October 2017, Marine Science Surveys were conducted around The Noises which provide evidence of diverse biogenic habitats present at The Noises which are particularly important to protect within the context of the wider Hauraki Gulf.

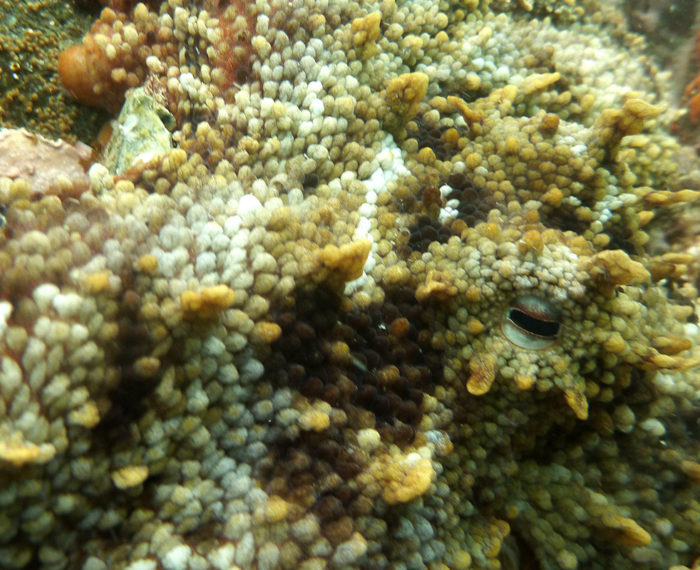

Octopus. Photo: Tim Haggitt.

Seabirds

Seabirds are a crucial component of healthy ecosystems. They are what biologists call keystone species because they have a powerful influence on the functioning of the habitat around them. In the case of the Hauraki Gulf, seabirds link the land and sea.

The Noises provide safe breeding grounds for the highest number of seabird species in the inner Hauraki Gulf. Ruapuke/Maria Island is one of only six confirmed breeding sites of the takahikare/white-faced storm petrel in the region (Gaskin & Rayner 2013). The oi/grey-faced petrel breed on both large islands and other nesting species include the kuaka/northern diving petrel, pakaha/fluttering shearwater, korora/little blue penguin, tara/white-fronted tern, black-backed gull, tarapunga/red-billed gull, kawau paka/little shag, and the karuhiruhi/pied shag.

All these species are extremely vulnerable to introduced mammal predators such as mice, rats, stoats, and cats which eat their eggs, chicks, and even adult birds.The removal of these pests from The Noises saw a substantial increase in breeding populations.

Whilst seabirds spend most of their lives on the ocean, they remain tied to breeding sites on land, and it is in the safety of predator free islands, such as The Noises, where they nest on the surface or in burrows.

During the breeding season seabirds return to the islands to their incubation duties and to feed their chicks. Some species, such as takahikare/white-faced storm and pakaha/fluttering shearwater, only come ashore at night when they dig nesting burrows. They also mill around on the forest floor, socialising, preening, scrapping, and resting. Others, such as Tara/white-fronted tern, and tarapunga/red-billed gull, nest in dense noisy colonies on cliffs and rock stacks.

Most importantly, the birds leave behind on the land a rich top dressing of poo (guano). Seabird guano is rich in nutrients harvested from the sea such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Whether deposited on the surface or burrowed into the soil these nutrients help fire up island forests. On predator free seabird islands, the plants thrive in rich soil. The benefits roll on to the invertebrates, the reptiles and the land birds. Run off of nutrients into the surrounding sea feeds the undersea seaweed forests benefitting all near-shore marine life, which (if protected) contributes to flourishing marine ecosystems.

The story is echoed on seabird islands throughout the Hauraki Gulf, such as Hauturu o Toi/Little Barrier, and across New Zealand. Seabirds represent half of New Zealand’s endemic species and the Hauraki Gulf is considered a globally significant hot spot for seabirds.

Spotted shag. Photo: Jason Hosking.

Takahikare/white-faced storm petrel. Photo: Edin Whitehead.